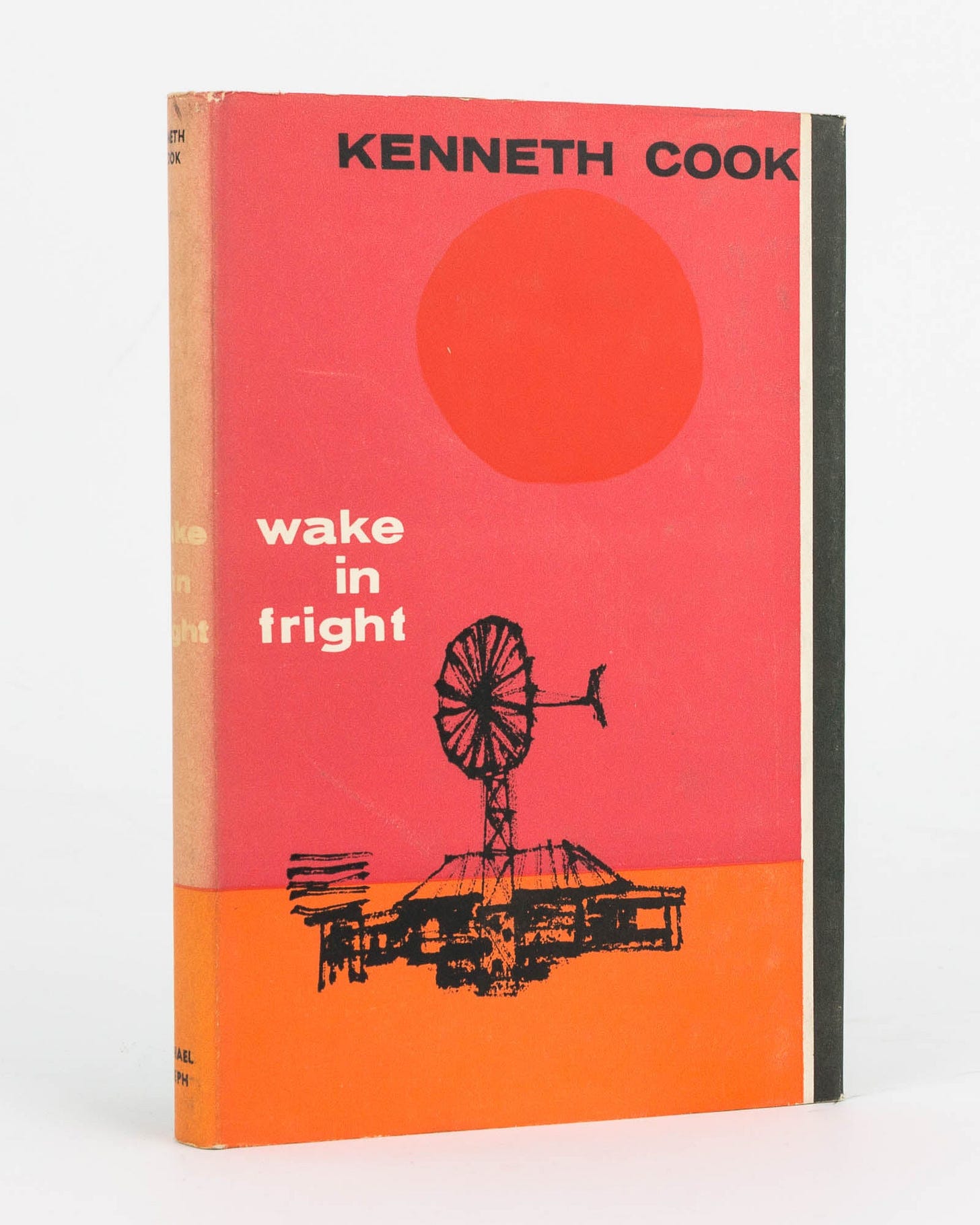

No Substance #170: The Two Visions of Wake in Fright

Wake in Fright opens in a one room school in Tiboonda, in the middle of nowhere. It’s hot. A drought is taking place and the land around it is flat, red, and empty. A single train track runs though the middle of the town. In the schoolhouse, the children are waiting for the bell to ring. It’ll signal the end of year. A young teacher, John Grant, is wait…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to No Substance to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.