No Substance #182: The Long Lie of Forrest Carter, Part 1

(Today I have a long essay to share with you. It’s so long I thought it best to cut it into two newsletters, this one and the next. The whole essay is about Forrest Carter, one of the great literary hoaxes and a truly terrible person. So, naturally, please enjoy.)

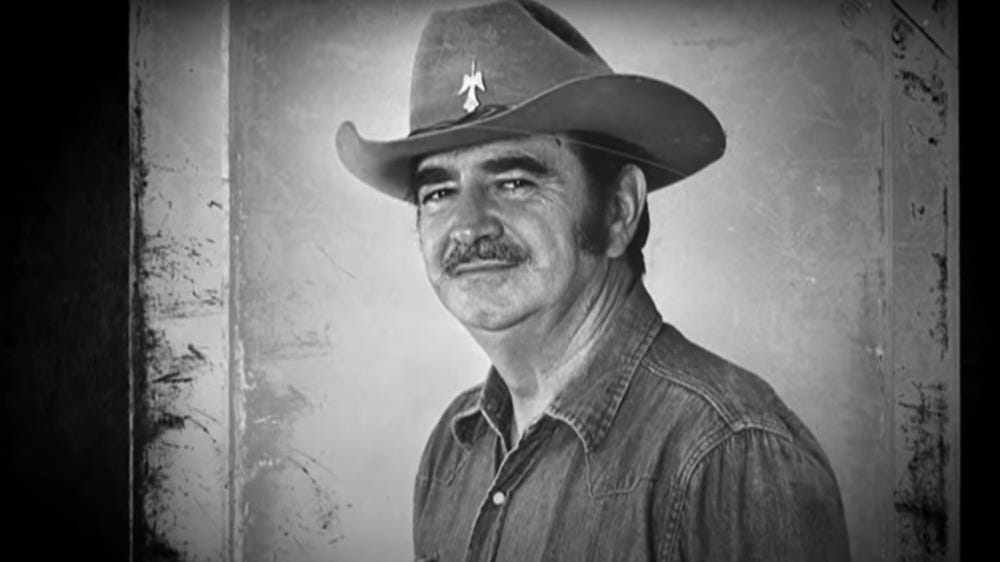

Forrest Carter, the author of The Education of Little Tree and The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wale…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to No Substance to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.