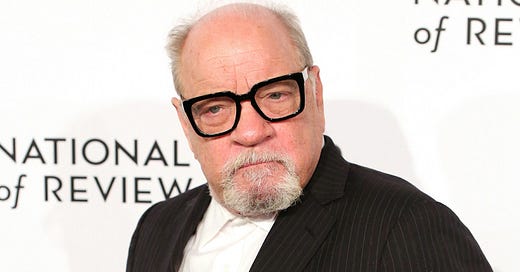

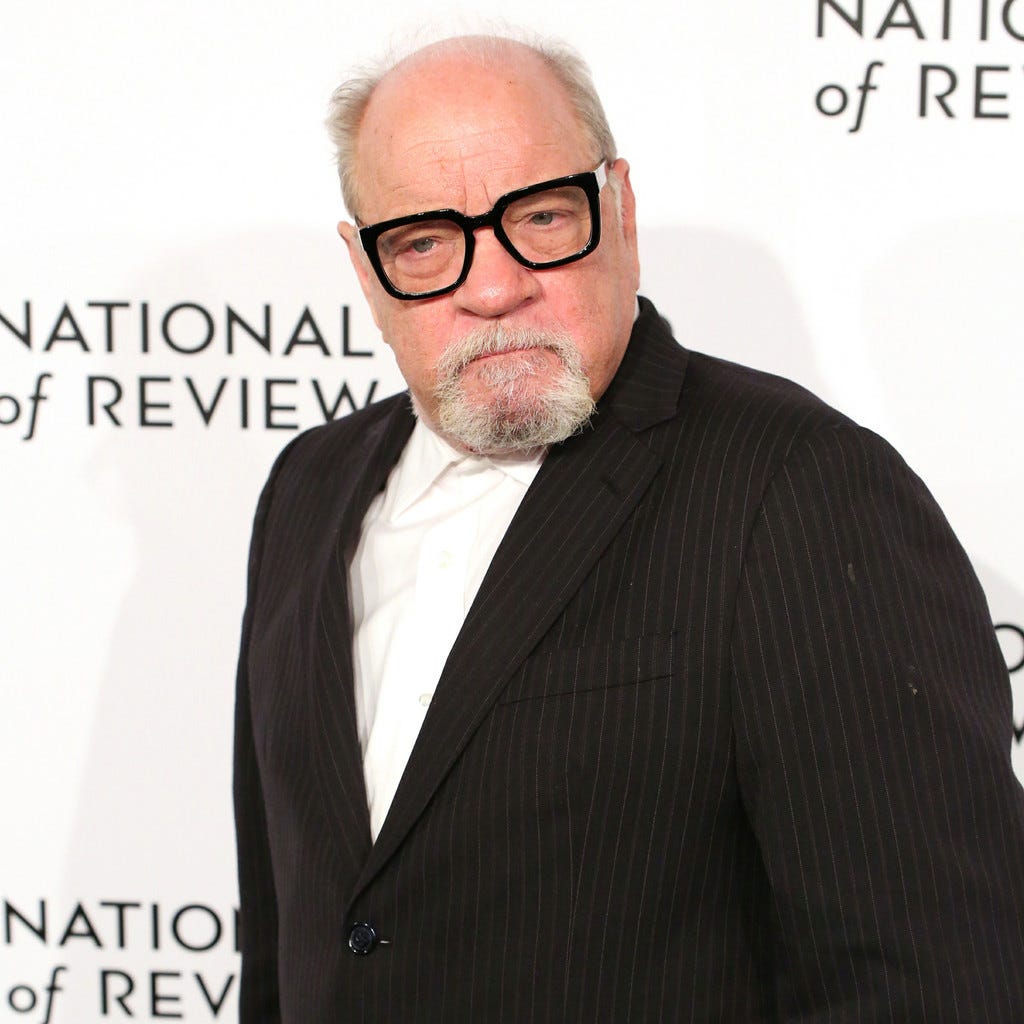

A couple of days ago, a news story broke about sexual allegations involving 78 year old Paul Schrader, director of First Reformed, Afflicted, and Hardcore, to name but a few of the films he has made. I say allegations, but they aren’t really, because the details of the allegations have been agreed upon by Schrader and his unnamed assistant, 26. In a confidential settlement, Schrader agreed that he sexually assaulted his assistant and subjected her to sexual harassment during the tenure of her employment with him. He agreed to pay his former assistant compensation only to later refuse to do so. This thus saw his assistant’s lawyers apply for a court order to pay the agreed settlement. In doing so, the story became public.

If you don’t know Schrader by the films I listed, or any of the others on his CV (American Gigolo, Auto Focus, The Canyons, etc), you probably have come into contact with his work as a scriptwriter. His most famous script is that of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, a relationship that continued with Raging Bull, The Last Temptation of Christ, and Bringing Out the Dead. He also wrote Mosquito Coast, and The Yakuza. His body of work is, by any standard, excellent and, despite the misses, remains interesting throughout.

It is also, like so many of these men who are found to be sexual predators, or pests, a body of work that casts Schrader’s own behaviour as villainous.

I suppose it shouldn’t be all that surprising. I don’t have any real interest in work that promotes the idea that it’s fine to assault and harass your assistant, or take advantage of anyone around you because of your position, your wealth, or your privilege. But then, that work doesn’t really exist outside a few sexual fetishes, and even then, the proposition isn’t taken seriously. It’s not an extreme view, or outrageous statement to say that you shouldn’t force yourself on someone physically, or use your power or wealth to do so. Likewise, you shouldn’t make things uncomfortable for people by saying all sorts of shit that they don’t want to hear. We all agree that that is unacceptable, that it is shit and criminal and life would be way better if people didn’t do it. And yet, we all know someone, don’t we? If not personally, then publicly, we know someone who does this. They’re mostly men, as we all know.

Schrader’s work is often centred around outsiders, usually lonely, or isolated men. In the last film of Schrader’s I watched, The Card Counter, he presents William Tell, an ex-soldier convicted of war crimes who, after he is released from prison, becomes a gambler intent on getting revenge on the man he believes responsible for his own downfall. Before that, in First Reformed, Schrader presented a reverend who finds himself struggling to make sense of the state of the world after a man he tried to help kills himself. Another isolated man, he is trying to make sense of a world marked by violence and ecological disaster and his own mortality and addictions.

These kind of characters exist, again and again, throughout Schrader’s work, but so do the women who appear in them as well. Schrader’s female characters are often the saviours of these lonely men, or are perceived, as in Taxi Driver’s, to be their saviour. Rightly or wrongly, they become representative of the better part of their male counterpart, and are often responsible for drawing that out, or bringing in new experiences, and delivering the notions that these men can be saved. These female characters sometimes verge on being a cliché versions of the prostitute with a heart of gold, as shown by Niki in Hardcore, one of Schrader’s early films. But regardless of that criticism, you would argue that, within Schrader’s work, there is a respect for women within it, and that they often present the better parts of humanity he depicts.

The point I find most interesting, though, is that within the Schrader’s own world, the one mapped out on the screen, or within words, Paul Schrader’s own behaviour is unacceptable. Schrader might be, unlike Neil Gaiman (currently trying to get his court case moved to New Zealand, fyi), be the main character of a film he’d a make, an old, lonely film maker who assaults a young woman, but he wouldn’t be presented well, or his behaviour justified. Within a Schrader narrative, he would seek redemption and be damned with or without it. In comparison, Neil Gaiman would never appear as a protagonist in a Neil Gaiman work. The man who sexually assaults a nanny, or convinces a woman to engage in sex to keep her home, would be cast as a villain. He would be punished, rightly so, within the narrative. So would Schrader punish such a figure. Both of the narratives would hit the same end point, in that the behaviour exhibited by the character would be deemed unacceptable within the work, and the Paul Schrader or Neil Gaiman who wandered the screen or pages, would suffer.

Most likely, he would suffer horribly.

A work is not representative of its creator. Heinous people make beautiful things. Wonderful people make terrible things. I know this. I accept this. I don’t look through the work of artists who turn out to be bastards for all the hints that suggest this was the real them and they’d hidden it from us for so long. There’s no point in that, I think. Any instance of it is often fools gold, anyway. Instead, what I find interesting in the case of Paul Schrader and Neil Gaiman and all the other artists I’ve talked about here and others I haven’t, is how their work sets up a condemnation of their own behaviour and how they believe that condemnation outside it, just as readers do. To engage in their work is to find them guilty of their crimes, even as they (inevitably) claim their innocence.

It’s a fascinating narrative that exists outside their crimes, one that isn’t of importance to real life, but rests in their artistic life and the legacy that they will leave behind once they are gone. In their own way, their work becomes their own jury, and it judges them well before any day in court, and it never judges them kindly.

Ben

(Ben Peek is the author of The Godless, Twenty-Six Lies/One Truth, and Dead Americans and Other Stories, amongst others. His next book will be The Red Labyrinth. His short fiction has appeared in Lightspeed, Clarkesworld, Nightmare, Polyphony, and Overland, as well as various Year’s Best Books. He’s the creator of the psychogeography ‘zine The Urban Sprawl Project. He also wrote an autobiographical comic called Nowhere Near Savannah, illustrated by Anna Brown. He lives in Sydney, Australia.)