No Substance #98: Neil Gaiman's The Sandman, A Re-Read, Part 2

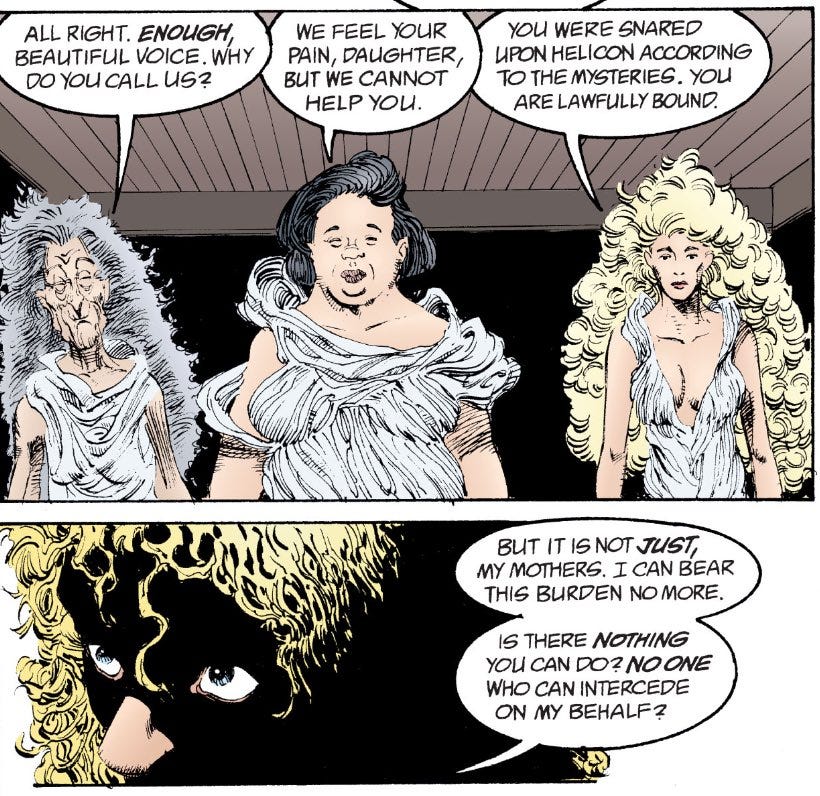

After the completion of The Doll’s House story line in The Sandman, Neil Gaiman tells a story about the muse, Calliope, the muse who was said to have inspired Homer.

Some time in 1927 Calliope returned to Earth briefly and was captured by a writer called Erasmus Fry. When we met Fry, he is an old, unpleasant man whose work is out of print and who, as a w…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to No Substance to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.