No Substance #183: The Long Lie of Forrest Carter, Part 2

(Below is part two of my essay on Forrest Carter. The first part is here, in last week’s newsletter, if you missed it. Otherwise, I hope you enjoy.)

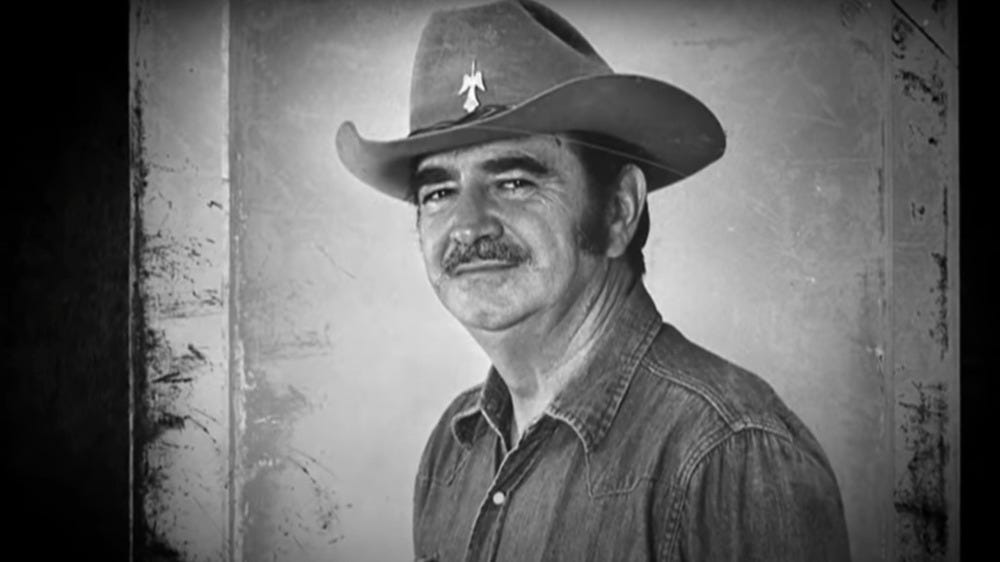

Forrest Carter is a successful author.

When you write about Carter, you’re not writing about an obscure American author, one whose work has no clear and visible footprint in the country’s culture. The fiftiet…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to No Substance to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.